Lose Together, Thrive Together

The New Year is a time for fresh starts and setting meaningful goals. If weight loss has been a challenge, 2025 could be your breakthrough year with the help of weight loss surgery.

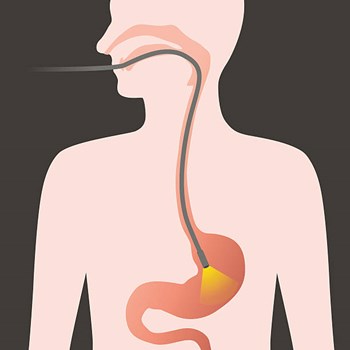

Eviva can perform endoscopy procedures in our comfortable outpatient surgical center.

Upper endoscopy enables the physician to look inside the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum (first part of the small intestine). The procedure might be used to discover the reason for swallowing difficulties, nausea, vomiting, reflux, bleeding, indigestion, abdominal pain, or chest pain. Upper endoscopy is also called EGD, which stands for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (eh-SAH-fuh-goh-GAS-troh-doo-AH-duh-NAH-skuh-pee).

For the procedure, you will swallow a thin, flexible, lighted tube called an endoscope (EN-doh-skope). Right before the procedure, the physician will spray your throat with a numbing agent that may help prevent gagging. You may also receive pain medicine and a sedative to help you relax during the exam. The endoscope transmits an image of the inside of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, so the physician can carefully examine the lining of these organs. The scope also blows air into the stomach; this expands the folds of tissue and makes it easier for the physician to examine the stomach.

The physician can see abnormalities, like inflammation or bleeding, through the endoscope that don’t show up well on X-rays. The physician can also insert instruments into the scope to treat bleeding abnormalities or remove samples of tissue (biopsy) for further tests.

Possible complications of upper endoscopy include bleeding and puncture of the stomach lining. However, such complications are rare. Most people will probably have nothing more than a mild sore throat after the procedure.

The procedure takes 20 to 30 minutes. Because you will be sedated, you will need to rest at the endoscopy facility for one to two hours until the medication wears off.

Preparation

Your stomach and duodenum must be empty for the procedure to be thorough and safe, so you will not be able to eat or drink anything for at least six hours beforehand. Also, you must arrange for someone to take you home—you will not be allowed to drive because of the sedatives. Your physician may give you other special instructions.

The New Year is a time for fresh starts and setting meaningful goals. If weight loss has been a challenge, 2025 could be your breakthrough year with the help of weight loss surgery.